All texts copyright Richard Shillitoe

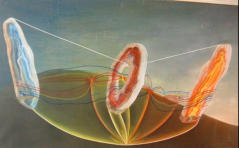

sunset birth

c.1942

Oil on canvas.

15½ x 28in. (39.3 x 71.2cm.)

Signed and inscribed on the frame: ‘Ithell Colquhoun/The Sunset Birth’. Signed again on the stretcher:

‘Ithell Colquhoun’.

Provenance

Christie’s, 3 June 1999, lot 213, ill. col.

Private collection.

Exhibited

London, The Leicester Galleries, 1942, no. 32.

London, International Art Centre, 1942, no. 5.

Colquhoun painted or sketched the Men an Tol, an enigmatic megalithic monument sited in West Penwith,

Cornwall on a number of occasions, but this is the only time she painted it in oil.

The site consists of an upright, circular granite slab, just over one metre high, with a circular hole 46cm.

in diameter. It is flanked by an upright stone at the North East and another at the South West. The holed

stone is believed to be an eroded-through solution basin from a local tor stack. Set upright in an inversion

of its natural horizontal state, ‘a form that once held water has now become dry, transformed into a

material metaphor for the rising and setting of the sun at important times of the year.’ (1) The site is

unique, although there are doubts concerning the extent to which its modern appearance conforms to the

original prehistoric configuration. Its original purpose is also the subject of conjecture.

The overall NW/SW axis lies in the direction of the midsummer sunrise and the midwinter sunset. The

monument has attracted folklore concerning the healing powers of the stones, especially for ailing

children and barren women. According to Cornish folklore, babies could be cured of ailments by being

passed through the central holed stone of the monument ‘against the sun’ (i.e. from West to East) in

what is a symbolic act of rebirth. Colquhoun mentions the folktale in The Living Stones. This painting,

however, refers to the folk belief that crawling through the holed stone could cure infertility.

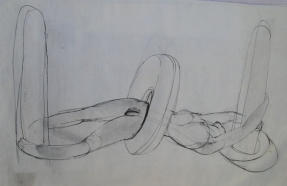

Several studies show how the imagery developed. The first, a

substantial ink drawing, shows a naked woman, flat on her

back, stretched through the holed stone. She reaches out and

clutches one of the uprights in her arms whilst holding on to

the other vertical stone with her feet. The second study, a

watercolour, shows lines of force travelling along the woman’s

body and establishing contact with the two standing stones.

The lines are bundled into nodal points at the areas of the

genitalia, navel and breast. A small sketch on the same sheet

shows the force field penetrating deep into the earth, or,

more correctly, emerging from a point deep within it. In a further watercolour, the stones are

coloured for the first time, in the hermetically significant colours of red, blue and yellow.

The painting contains detailed references to the Tantric system of the chakras. According to Tantra, an

inner structure of channels (nadis) pervades the body (more accurately, the subtle body), allowing it to

receive and distribute vital energy. Some of this energy is solar in origin, whilst other energy comes from

deep within the earth. Three main nadis run along the spinal column in curved paths, crossing one

another several times. At the points of intersection the nadis form strong energy centres known as

chakras. The three spinal channels are Sushumna, (deep blue), Ida, the feminine aspect of the force

(crimson in colour) and Pingala, the masculine aspect (yellow). The colours of the nadis, the subterranean

origin of energy and the chakras are all visible in the outlines of the woman’s elongated body.

In the final painting, the outline of the woman’s body has all but disappeared: only an ethereal memory of

her physical presence remains in the glowing stones and flowing currents.

notes

1. Tilley, C. and Bennett, W. An Archaeology of Supernatural Places: the Case of West Penwith. J. Roy.

Anthropological Institute (NS). 7: 335-362, 2001.